Editor: From the Travelodium Archive this article was first published in 2009.

When we told our friends about our adopted hometown, they were horrified. “There’s no cinema! No nightclubs! Not even a museum! What on earth do you do for entertainment?” They were living in Seoul, possibly one of the world’s most hectic capitals. We on the other hand were spending our year in Korea in a rather different setting.

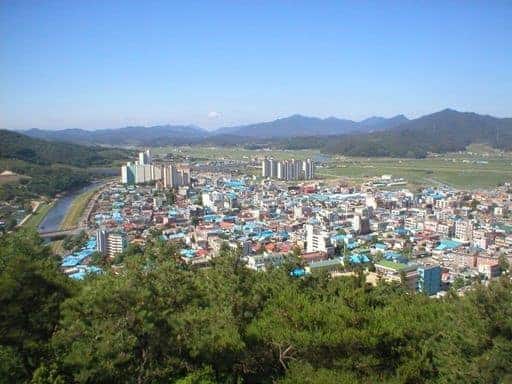

Cheongyang has a population of 12,000 and a surface area that means you can walk across the entire town in under 15 minutes. Where Seoul boasts wall to wall restaurants, bars, nightclubs and norae bang (karaoke rooms), Cheongyang’s attractions are pretty but less than exhilarating: lots of hills, a few family-run eateries and a couple of well-kept riverbanks.

This was not our first choice of location. Before setting off to teach English in the Far East, we had spent weeks doing our homework. We’d agreed on a smallish city in the centre of the country, choosing it for its perfect population of 80,000 – not too hectic yet not a one-horse town. But on arrival in Korea we discovered our destination had been changed to a town so small that even the locals couldn’t pinpoint it on a map (or the space it would have occupied if it were large enough to cartographers to bother with).

Although the surroundings were pretty, we feared for our sanity in this tiny town, especially when we discovered that our arrival had just doubled Cheongyang’s English teaching population. With only two friends to count on until our Korean skills improved drastically, the pressure was high. EFL notoriously attracts a few unusual characters – what if our neighbours were weird, nuts or just plain unfriendly? The pressure to get along was piled on further when we realised we’d be neighbours. Our building housed just two apartments – us downstairs, our Canadian counterparts upstairs, meaning we’d see each other on a daily basis whether we wanted to or not.

We didn’t head upstairs to introduce ourselves straight away, delaying what could have been a disastrous meeting. But in such a tiny town you can’t avoid people for long; we met our new neighbours, Brett and Una, after just two days in Cheongyang. We were trying to work out exactly what it was that we’d just purchased in the town’s supermarket when they pounced on us, thrilled at the idea of English-speaking company. We instantly and blissfully discovered that our fears were unfounded; the four of us had all but everything in common and we soon became inseparable, wandering into each other’s apartments unannounced, attending essential language classes and dining out at the town’s traditional sit-on-the-floor restaurants.

So the town was pretty, the apartment a delight and the neighbours set to be friends for life – but just what do you do for entertainment in a town where a wild night out means a game of bowling, a take-away pizza and an early night? Well, the answer soon presented itself – as one of four foreigners in town you enjoy your new-found status as a local celebrity.

Brett and Una had been enjoying life in the spotlight for six months, but our initiation came soon after arriving when we attended a totem pole festival held in a nearby beauty spot. Until then I hadn’t realised how utterly isolated we were and had expected to see English teachers from surrounding towns enjoying the festival too, but it soon became evident that we were the only foreign faces there and I finally grasped that we were the only English teachers within a 40km radius.

This did not go unnoticed by the local press, who were following us en masse to snap shots for their respective magazines and newspapers. I was shocked at just how many journalists were attending this small-scale rural festival when Brett pointed out that these weren’t professional photographers at all – just curious locals with top-of-the-range cameras. I’m sure when you’re an A-list celebrity the Paparazzi can be tiresome, but in our year in Korea we never tired of posing for strangers’ photos – and they never tired of asking us to.

Back in town a couple of weeks later we had our first real brush with the local media. A journalist joined us for our customary evening beers and in broken English grilled the four of us on life in small town Korea. Once the article appeared, translators revealed the angle to us – we had been granted a full page of the local newspaper simply for being foreign. Later appearances in local rags were similarly newsworthy – our birthdays, the fact that the students liked our classes and most newsworthy of all, the fact that my boyfriend Shawn was very tall indeed.

As summer neared, the town’s bafflingly huge cultural centre opened and hosted a one-off performance of opera and classical music. Keen to join in with anything that wasn’t another Friday night sipping beers on patio furniture outside the Seven Eleven, we rushed to the free performance. And if we had ever wondered whether we’d be happier in a larger city, the response to us attending this event gave us our answer. Well, how often is it that the conductor and theatre manager approach members of the audience to pump their hands gleefully and thank them for coming?

But the real highlight of life in Cheongyang was the nightlife, low-key as it was. Of course, we didn’t have the option of cool bars, Irish pubs, wild clubs or even live music, choices that most people take for granted. Sometimes our ‘party’ nights featured little more than the four of us and a three litre pitcher of cheap and slightly flat beer. But whenever there were local revellers in the bars it led to some of our best nights out in Korea – always more memorable than the weekends rubbing shoulders with other westerners in central Seoul.

When we headed out, prepared for another quiet Saturday night, it was always a joy to find the bar filled with revellers enjoying a bachelor party, birthday party or work night out and even more of a joy to receive an invitation to join them. Considering themselves our hosts, the local folk wouldn’t take a single won of our money, pushing our wallets away as they refilled our glasses with soju, a potent and popular local liquor made of rice (and the culprit of some lethal hangovers). Conversation was often limited to drunken one-word utterances: “beer!” someone would shout, provoking a jubilant response of grinning and laughing, then our co-drinkers would turn expectantly to us. “Maekchu!” we’d respond, the first word we learned in Korean, and everyone would roar, slap backs and order yet another pitcher of maekchu.

So when those friends in Seoul asked what on earth we did to amuse ourselves in such a tiny town, we didn’t have to think long before responding: “We don’t need entertainment – when you’re one of just four non-Koreans in a town of curious and welcoming locals, you are the entertainment!”

I remember my initial horror as our co-teachers drove us to this backwater town that’s often missed off maps. I was planning my departure before I’d even arrived, but if I had my time over I wouldn’t change a thing. So many westerners who head to Asia to teach away their university debts head straight to the large cities, presuming that rural experience would be a backward and boring one. But there’s never anything boring about being a local celebrity, having strangers lining up to shake your hand or posing for photos with groups of giggling teenagers or slightly more serious businessmen. But fame aside, living far from big cities has another huge benefit – it allows you to delve deeper into local culture and get a truer experience of Korean life. You’re forced to learn the lingo and sample the food, for there are no chain restaurants or mammoth supermarkets to save you. Of course when it all gets too much you can always escape to the cities for a few home comforts, but after every trip to Seoul we were thrilled when the familiar sights of hills and tractors hailed our return to the back of beyond.